I wish to see art in Paris

Shelby

autoimmune disorder

Shelby pays it forward after art-inspired wish

She could do so many things that I couldn’t, like remembering all the capitals of all of the states and being able to name all of the past presidents, even the ones with the funny names, like Chester A. Arthur. She could write in the most beautiful loopy handwriting that always seemed to dance gracefully across the page. If you gave her a blank piece of paper and some crayons, even as a child her houses looked like houses and her dogs looked like dogs.

But I also knew that there were lots of things she couldn’t do. Shelby couldn’t run, or skip rope, ride a bike or play soccer. She couldn’t come to school for a long time when our entire classroom came down with the chicken pox. I never minded that. Shelby was always my superhero, the person I wanted to be when I grew up. I wanted to be brave and patient like she was; even when she was hurting, she never snapped or was mean. Even though she was diagnosed at a young age with an autoimmune disorder that I struggled to pronounce (and still have to google to be able to spell correctly: juvenile dermatomyositis), Shelby never let it slow her down. She conquered. She won spelling bees and drew increasingly beautiful pieces of art and sang with a clear, soprano voice.

We were thirteen when everything changed. While Shelby had always had health problems, she had generally been able to live her life with only a few adjustments for her limitations. Suddenly, those limitations were daunting. She couldn’t stand up long enough to take a shower anymore or hold her arms up to wash her hair. She couldn’t step up into her bed. We made more changes and tried to make her life manageable again. I commissioned a friend to make her a long wooden step to help her get in and out of bed. Our mother found a shower chair so that she could sit and bathe. We adjusted.

But then the worst thing of all happened: Shelby couldn’t hold a paintbrush or a pencil anymore. Her hands ached too badly for her to have the fine motor control she needed to make her art. I watched a piece of my beautiful, talented sister slowly die during that time. She went into a deep depression and I didn’t know if we’d ever get her back again. She was on so much medication and she was so sick and weak all the time. I had always been her warrior, her protector, and I felt utterly helpless. I didn’t know how to help her through this.

Thankfully, somebody else did. Shelby’s occupational therapist, an old family friend, referred her to Make-A-Wish. When they asked her what she wanted most in the world, a bit of Shelby’s spark came back to her. She wished for the moon: she wanted to go to Paris to see all the art she’d always dreamed of and read about in books. Privately, our family didn't think a wish like that would happen. It was too expensive, too far, too much to ask for, but Make-A-Wish just said, “let’s make it happen.”

And they did. The Germantown Chamber of Commerce sponsored my sister’s wish to go to Paris. They threw a wonderful reveal party where a caricaturist drew pictures of all of Shelby’s friends (and then patiently sat while Shelby slowly drew a caricature of him in return). I will never forget the look on my sister’s face when she was told that she would be going to Paris. It was pure joy and even more: it was hope. We hadn’t had any of that in what felt like a very long time.

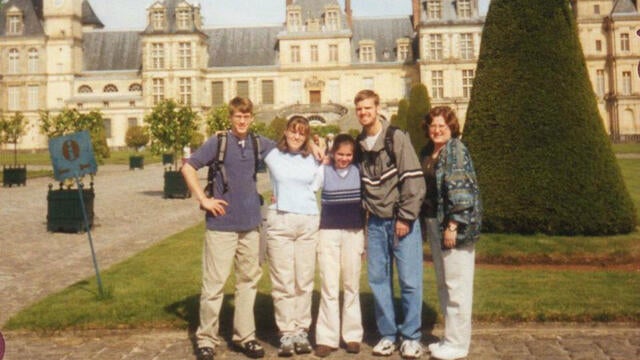

I could write a whole book of that wonderful trip to Paris. We laughingly stayed in a hotel called “The Hotel California” and hummed the song to our confused taxi drivers whenever we were ready to return after a long day of sightseeing. We went to Versailles, to Normandy, to the Musee D’Orsay and to Notre Dame. Shelby had been studying like a demon in the weeks leading up to the trip and frequently impressed (and annoyed) our tour guides by knowing more about French history than they did. She devoured the art and scribbled down all the details of each day at night in a journal before she went to sleep. She came alive.

In the years after our return, Shelby, truly paid it forward, and her health improved enough for her to draw again. She donated nearly 100 pieces of art to Make-A-Wish to be auctioned and succeeded in making enough money for the organization to grant multiple wishes. After her wish, she could draw and paint and dance and get in and out of bed every morning again. She had hope.

It’s been sixteen years since that trip to Paris. Shelby went on to earn first two bachelor’s degrees from Union University, then two master’s degrees (one each from the University of Tennessee and Vanderbilt University), and last month she triumphantly graduated from Vanderbilt University with a doctorate in English Literature. She just accepted a position on the faculty of Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton. Even better, she has since been determined to be in remission from her illness.

I firmly believe that none of this would have been possible without Make-A-Wish. Shelby went from a place of deep depression to finding joy in her life again. I don’t know if anything else would have been capable of reaching her. I will be grateful to Make-A-Wish for the rest of my life for giving me back my sister, and for our doctor who encouraged us to learn more about Make-A-Wish. Shelby never stopped being a superhero; she just needed a little help remembering how to fly.